How a Simple Bash Prompt became a complicated problem

tl;dr: This is a ´problem -> solution´ type post, reflecting on problems I encountered while writing a bash prompt generator.

A small need for a more informative prompt

This all started about 10 years ago when I was working as a Java consultant in Oslo. We had just moved from SVN to git, and the concept of feature branches was suddenly a thing. I hadn’t really been very involved with VCS before git, but now I felt like I understood it. (I didn’t). So I wanted to add the current git branch to my prompt. I quickly ended up with something like this:

PS1='\u@\h:\w$(git status 2>/dev/null | sed -n "s/On branch \(.*\)/ [\1]/p") '

This basically says that my prompt should be my ‘my_user@my_host:my_working_dir’ and if the git status command gives us data, insert the branch in [brackets]. Pretty simple, but with one gotcha. Notice that the value of the ´PS1´ variable is enclosed in single quotes. This is because the ´PS1´ variable is evaluated when printing the prompt. If I had used single quotes the subshell expression ´$()´ would have been evaluated only once and my git status would never have changed.

Anyway, I was quite content with this until one of my colleagues installed oh-my-zsh and I was blown away by how great it looked. I quickly ditched my old prompt, installed zsh and installed one of the powerline themes. It looked great, but I just didn’t like zsh. To me it felt like moving from Python to Ruby, everything was similar, but felt different in a fundamental way. So everything that I’d learned about Bash, suddenly didn’t work the same anymore. Every 3 years or so I try moving to zsh but always come back after a day or so. I guess I’m stuck here with Bash.

The quest for a Powerline prompt in Bash

I started searching for a bash equivalent of the powerline prompt and I stumbled upon powerline-shell, which looked perfect, but it was quite slow. It was also written in python, which I found to be suboptimal as I wanted to be able to quickly add new segments by just relying on the cli tools already available. Bash is great for this.

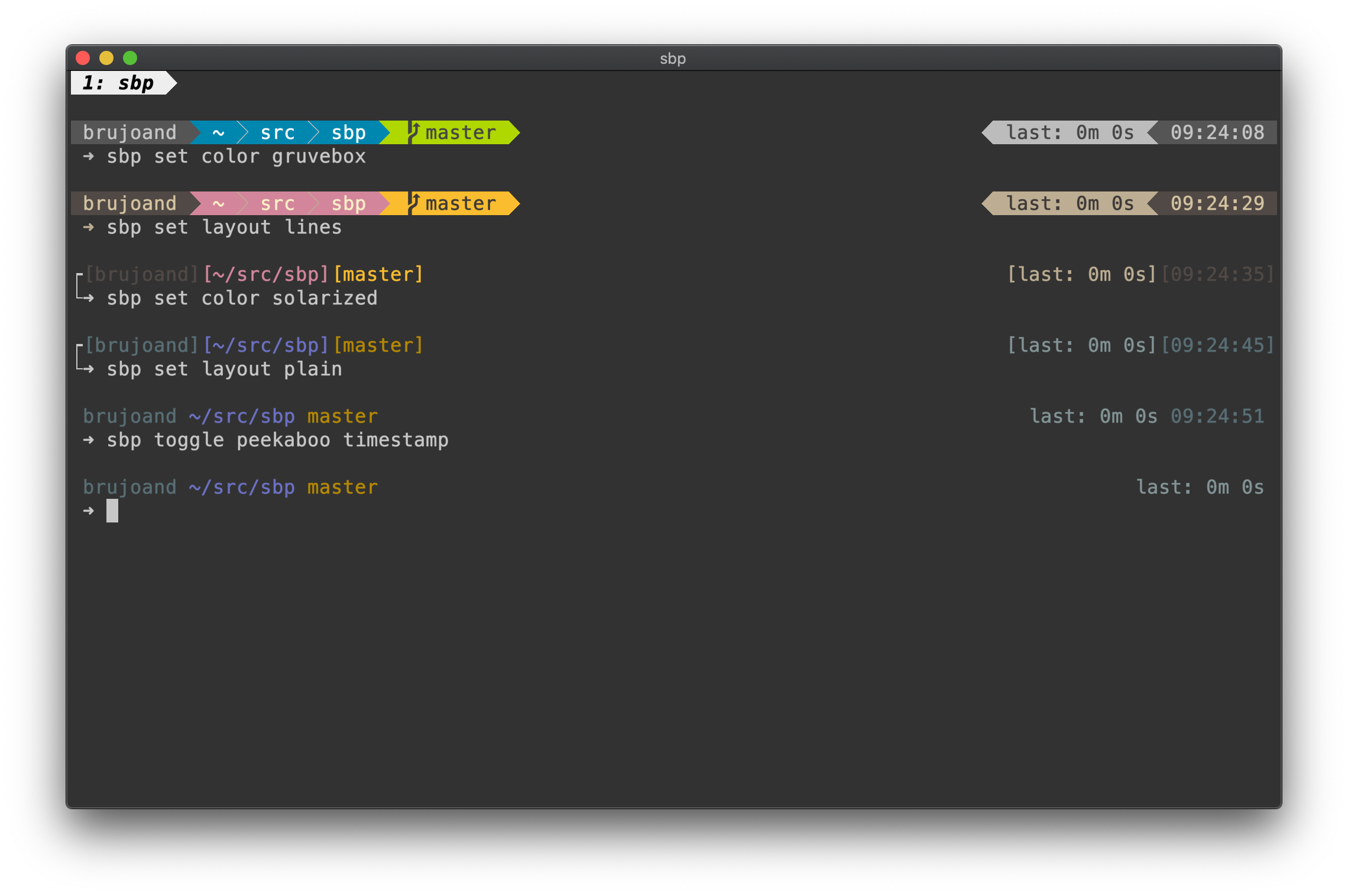

After a while I gave up my search and tried making my own Simple Bash Prompt. The first version was a 500 line shell script which was meant to be evaluated at the prompt draw time like so ´PS1=’$(generate_prompt $?)’´. Basically call my ´generate_prompt´ function with the exit code of the last command as the only parameter. This allowed me to change the appearance of the prompt based on the success or failure of the previous command. As the project grew I added configuration options, color schemes and predefined layouts. Below are some of the challenges I’ve been pulling my hair out over and how I solved them.

The SBP requirements

- It must render in less than 100ms (Preferably 50ms, less is more etc)

- The code must be easy to read and test

- The prompt must be easy to extend and adapt

- The prompt should be reactive, meaning the layout could change if the screen size shrinks.

Writing clean and fast code in Bash

A Bash prompt written in Bash makes sense if you want it to be portable and easy to use. But 1000 lines of Bash is not very readable, and hard to maintain. So you end up splitting logic up into re-usable functions and files that become small libraries for functions with a similar use cases.

But every variable="$(some_helper_function "$my_var")" will create a subshell, and they

are expensive. On my Macbook Pro a subshell costs about 1 ms, on my raspberry

pi the price is 4 times higher. This is made worse by avoiding repetitive code,

a common best practice, which results in more subshells when using helper

functions instead of just repeating the logic.

So I ended up relying on pass by reference for returning values without spawing a subshell. Example:

# Returning value by referencing the $1 variable

add_numbers() {

local -n add_numbers_result=$1

local first_number=$2

local second_number=$3

add_numbers_result=$(( first_number + second_number ))

}

# Passing a variable for the return value

print_numbers() {

local my_added_numbers

add_numbers 'my_added_numbers' 22 33

echo "$my_added_numbers"

}

print_numbers

# The output will now be: 55

So to avoid making the code more magic than necessary a few conventions are used. The first argument is always the name of the return value, and the return variable is always called ´${name_of_function}_result´. The ´-n´ flag was added to ´local´ in Bash 4.3 and basically says “create this variable and have it point to the variable who’s name is on the right hand side of the equal sign”. It does make the code less readable, and harder to follow, but this change alone reduced the execution time from ~180ms to ~50ms. A substantial reduction in execution time.

Another cost is structuring code in separate files so that logically close functions live together. This is again a ‘clean code’ practice that will incur a cost because now the file needs to be sourced every time it’s needed, however this cost is a lot lower and mainly affects readability as they file is read from disk once and usually kept in memory. There already exists a common best practice for this which I’ve adopted. In a script file called ´execution.bash´ the function names will be prefixed with ´execution::${name_of_function}´. This makes it much easier to track down where a function is defined, and it also avoids problems with naming collisions.

Concurrency in Bash

To be able to generate every segment of the prompt as quickly as possible, concurrency is needed as just evaluating a simple function that checks some environment variables and returns a string will hit 10ms easily. 10 of those and we’ve already hit our roof of 100ms.

Concurrency in Bash is easy if you just want to run a bunch of jobs in the background and wait until they’re finished. But if you care about their exit status and output it becomes a bit more tricky.

execute_segment_script "$segment" "$direction" "$max_length" > "${tempdir}/${i}" & pids[i]=$!

This obscurity is how I start a segment generation, output to a tempfile, and store the pid in an array.

for i in "${!pids[@]}"; do

wait "${pids[i]}"

# Add it to the prompt

done

This way we are more or less only bound by the speed of the slowest segment. Ideally we would be able to wait on all pids and handle them one by one as they exit, but I haven’t found a way to do that. I’ve tried using named pipes, and have each concurrent segment write to it on completion, while a second process reads from the pipe until all segments are done, but that was actually slower than the current implementation. xargs and Parallel could have potentially helped a bit by implementing a thread pool, but none of them really solves the optimized waiting and output handling. In addition, Parallel is not available everywhere. We also have Coproc but in our case it doesn’t really add anything that we don’t already have in the above solution.

Using nohup for functions you want to fire and forget

So you might have seen someone do something like this ´nohup my_command &´. The command ´my_command´ is executed in the background and no longer attached to the current shell, so it will live on even if our shell exits. This is great for executing scripts, but as it will create a new bash process it will not have the sourced functions from SBP available. Instead I found a neat trick on StackOverflow which lead to this:

execute::nohup_function() {

(trap '' HUP INT

"$@"

) </dev/null &>>"${SBP_CONFIG}/hook.log" &

}

This function will execute the command in a subshell, meaning our environment and functions are still available. The trap signal will catch the SIGHUP and SIGINT signals and ignore them. We disconnect our forked process from stdin by pointing stdin to /dev/null. We point stderr and stdout to ´${SBP_CONFIG}/nohup.log´ and we mark this command to be executed asynchronously with ´&´. Pretty nifty.

Avoiding external commands

Another approach has been to remove the use of external programs in favor of Bash builtins. This has added a lot of speed in many places as you can usually replace most grep/sed/awk expressions with parameter expansion. As an example consider replacing ´$HOME´ with ´~´ in your ´$PWD´:

➜ time sed "s|$HOME|\~|" <<< $PWD

~/src/sbp

real 0m0.005s

user 0m0.001s

sys 0m0.003s

➜ time echo ${PWD/${HOME}/\~}

~/src/sbp

real 0m0.000s

user 0m0.000s

sys 0m0.000s

I’d argue that this is both faster and more readable, although I’ll admit that parameter expansion is not always easy to read if you’re not familiar with the syntax. Note that I had to use ´|´ instead of ´/´ in the sed expression as my ´$HOME´ variable contains ´/´ slash which would have broken the sed syntax. Also I’ve used double quotes around the sed expression to allow for the use of a shell variable and the ´«< $variable´ expression let’s sed treat our variable as a file.

But for complicated search and replace like this sed to remove all color (and surrounding escape brackets) it wasn’t as straight forward.

strip_escaped_colors() {

sed -E 's/\\\[\\e\[[0123456789]([0123456789;])+m\\\]//g' <<< "$1"

}

For my entire $PS1 this takes about 6ms on my Macbook Pro as opposed to 12

seconds using bash parameter expansion.

Breaking readline by accident when adding colors

The above sed expression was necessary because I like having prompt segments both on the left and right hand side of the screen. To do this I need to know the length of the left and right segment strings and the width of the screen. The problem though, is that if you try to calculate the length of a string which contains escape sequences, strange things start to happen.

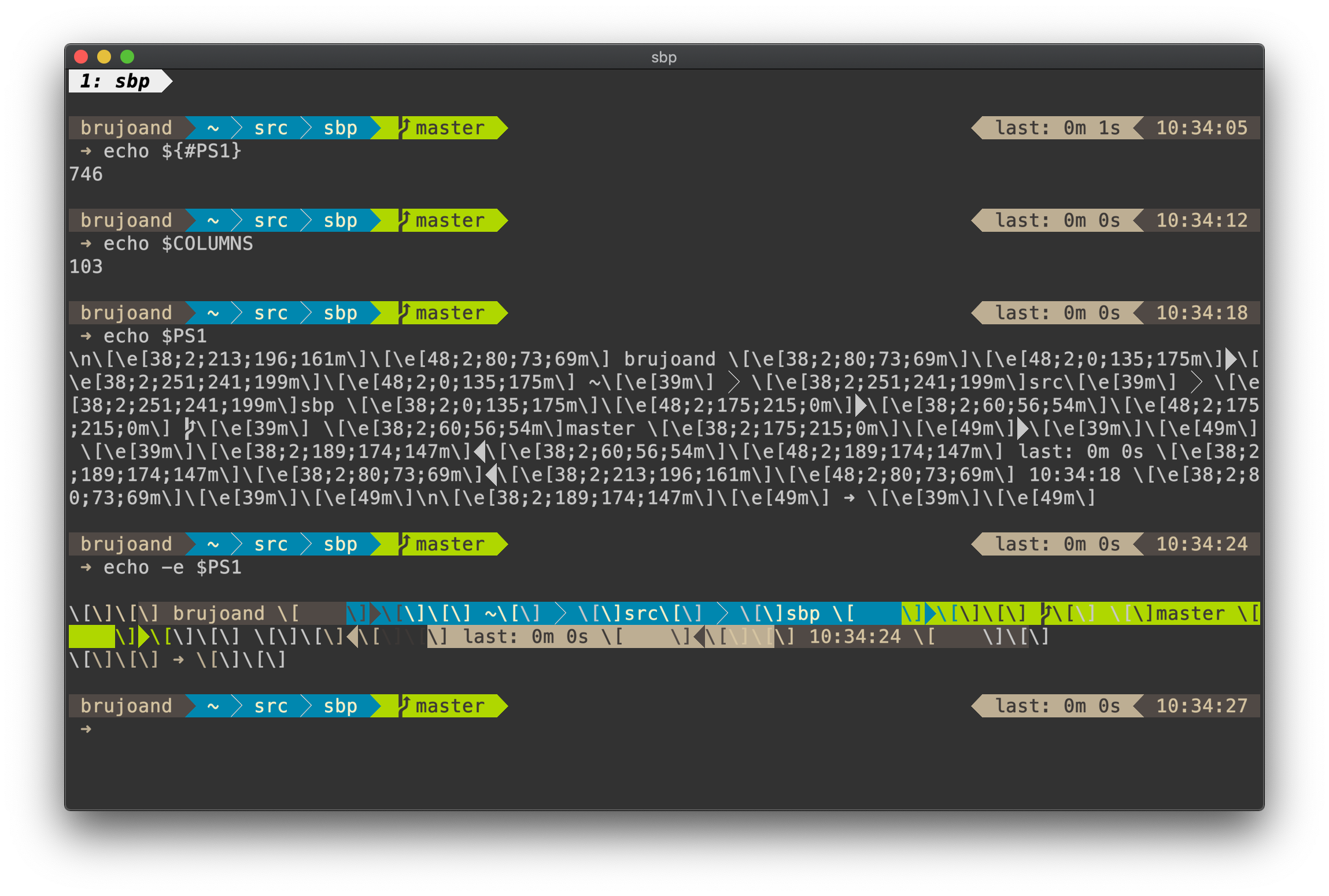

As you can see our ´PS1´ has a length of 746 which should be more than 7 rows divided on our 103 character screen width. Obviously this is not what’s happening and when we print ´PS1´ we see that there are a bunch of escape characters here. The expression ´\e[38;2;213;196;161m´ should be fairly recognizable to most. The ´\e[´ (escape + bracket open) is called a ‘Control Sequence Introducer’ and tells the terminal that here comes a command where the arguments are separated by ‘;’. The first number 38 means ‘set foreground color’, 48 would be background color. The second number is 2 and means that we will be printing an rgb color, a 5 would mean regular ansi color. The three next values are the respective rgb values, or single ansi color value if the previous value was 5. The sequence is terminated by the letter ´m´.

When we try to print the ´PS1´ variable with ´echo -e´ we will get the evaluated values of the colors, but still there are unevaluated escapes in our output. This is actually how readline keeps control over the current cursor position on the screen when printing color sequences. Every color definition needs to be surrounded by escapes so that readline doesn’t count it as a ‘printed character’. This means we need to print our color like this: ´[\e[38;2;213;196;161m]´. Failing to take this into account will cause weird problems like not being able to erase a command or suddenly have a new line appear in the middle of tying.

The sed in the above section to remove escape sequences was slow, and had to be executed on every generated segment to be able to calculate the size of the segments and the distances between the left and right hand side. To avoid this all together I ended up adding colors as the last step, after checking the length of the uncolored segments. Much less magic, and much faster. Keep it simple, stupid.

Figuring out how long the previous user command took

So this was a tricky one and I started out doing something like so:

command_start="$(HISTTIMEFORMAT='%s ' history 1 | awk '{print $2}')"

command_end="$(date +%s)"

command_duration=$(( command_end - command_start ))

This works pretty well as long as the previous command is actually committed to history. In bash 4.4 we got the brand new ´PS0´ variable which is expanded right before executing a command. So in SBP I added this:

_sbp_pre_exec() {

date +%s > "${SBP_TMP}/execution"

}

PS0="\$(_sbp_pre_exec)"

We are basically just taking a timestamp and storing it, and we read it back when we are about to draw the prompt. Here instead of using single quotes I escaped the ´&´ sign. This means the string will not contain the evaluated value, but evaluating the string will execute the command. Just two ways of doing the same thing.

So is SBP perfect now?

Probably not. SBP has improved as my understanding of Bash has improved, greatly helped by ShellCheck btw which not only tells me when I’m wrong, but also how I’m wrong and how to be right. My focus now though is on getting more segments and making it easy to use. If you see something that could have been done in a better, cleaner or more efficient way, please send a PR or create an issue. :)

PS: If you however want to stick with zsh, and still want powerline and speed, I suggest you checkout Powerlevel10k.