Building a Delivery Platform

A journey begins

Almost 10 years ago I finished my Masters degree in Computer Science and started working as a consultant at KnowIt in Oslo. My team was in charge of developing the integration bus for the local municipality, and we had earned a lot of freedom with the client. We ran our own Hudson build server, we were early adopters of self hosted Github enterprise, and we deployed to production at will using a suite of in house ruby scripts. We had monitoring, logging and even configuration was provisioned through puppet. This was all thanks to a couple of very skilled people who pushed for this way of working, and we all really enjoyed it. It just made sense to us, even though we had never heard of DevOps. T

When I eventually moved on to new adventures I was surprised to learn that this was far from the norm. As a result I ended up trying to improve upon the delivery process wherever I worked. Eventually it became my full time job when I joined Schibsted to help create a Delivery Platform for about 1500 developers scattered around the globe. It was an awesome experience that one of my old co-workers have written well about here (Adevinta used to be a part of Schibsted btw) Based on my experiences there are a few key elements, or steps if you will to doing this well. And I want to try to explore and generalize theme here.

A Delivery What Now?

Unfortunately the tech industry and especially the part that deals with automating infrastructure and tooling is riddled with buzzwords and phrases that mean different things in different contexts. What I mean by a Delivery Platform is this; A set of tools and services that can be composed into a coherent and intuitive pipeline that brings source code into production in a safe, predictable and repeatable manner. A pipeline in this sense then becomes a list of tasks, where the output of previous tasks is the input for later tasks. These tasks can be chained and even trigger other pipelines. You are then left with a language which describes the entire process your application goes through.

Know where you are

If you don’t know where you are, there is no way you’ll figure where you need to go. So the top priority should be to get good automated dashboards that show our current state. Smashing is a great tool for this because it let’s you write simple jobs that extract data from your existing tools and it’s very easy to massage the data in any way you want and push it into graphs, speedometers or any visualization really. I’m a huge fan of Grafana, but when you are just starting out on this journey the world is a rough place, and you need to scrape logs, convert data and integrate with legacy tools that might not even have APIs. Well, you don’t have that kind of luxury early on.

The value here is to get a snapshot of the system, which things are slow, which are fast. Where should you focus your efforts first to get traction. There is also the inescapable truth that even though management cared enough about “DevOps” to hire you, they might not be so motivated if they can’t see any impact. Graphs are like a magic force to management. Use the force.

Interviewing members of various teams who will be using your platform will also give invaluable insight into the current frustrations and the hopes and dreams of your users. This is key later on when you might need to motivate them to on board. If it doesn’t provide added value to them, they will not spend time on adopting your tools. They in turn will probably have to justify spending time on improving their process, make sure you provide them with metrics and arguments to do so.

This knowledge lets you start planning out where you want to go, and what your missing to get there.

The Golden Path

There are typically two ways of building these platforms. Either you provide tooling and services only, and let each team pick and choose how they want to integrate. This gives the teams a lot of freedom and autonomy, but it comes with a cost. The teams suddenly own a lot of glue code to make their pipelines work. Who should keep it up to date? Who should ensure that it’s secure and that it follows best practices? In the best case scenario it’s a cooperation between the platform team and the developers. Worst case, it rots.

Instead I’ve become a fan of the Golden Path. The platform team defines a generic pipeline from source to production, that integrates with the common tooling and that integration is owned and provided by the platform team. A platform as a service, if you will. In this approach all teams will get your tooling for free, if they just follow the recommended approach. The drawback here which you will undoubtedly hear, is “but we don’t use x” or “but we want to use some specific features of product y”. The gut reaction to these objections are often defensive, but they shouldn’t be. The golden path should provide everything for free, but it should also be easy to step outside when needed. In so doing, the teams should be aware however, that they own that extra mile until they are back on our path.

An example is probably helpful. Let’s say that to enroll in your golden path,

all you need to do is to add a paas.yml to your git repo:

version: 2

application_name: 'dogfood-api'

And that’s it. This yaml file might actually just be an override to a default shared configuration that holds all the default integrations like static code analysis, vulnerability scans and how to deploy the application. At Schibsted we used fiaas for this. Usually the defaults wont be enough so you might want to override some of them like so:

version: 2

application_name: 'dogfood-api'

healthchecks:

liveness:

http:

path: /_/my_unconventional_health_check_path

ingress:

- host: dogfood-api.ingress.local

ports:

- target_port: 5678

replicas:

maximum: 10

minimum: 20

SonarQube:

- enabled: false

This worked very well for us by providing a fully working pipeline with little to no configuration, that takes your application all the way from source to running in production. But when needed the power of the underlying tools are readily available by using the k8s API for instance. In this way the teams get to decide on their own how much of their configuration and integrations they want to own.

What makes sense for one company might not fit another so this becomes an exercise in communication and analysis to find a golden path that will help the most teams in your company. One caveat with having these yaml files for defining how an application should be treated is that you might end up defining everything there. Lots of configuration that might be hard to change later.

Convention over configuration

What if you had to be reminded of all the conventions you rely on every day?

How would that influence your productivity?

I’m a big fan of convention over configuration and if you manage to

utilize that, it will be much easier to add tools and services later without

adding extra specific configuration. For instance our dogfood-api could

generate a maven artifact named no.company.git_org:git_repo and when

integrating with SonarQube for instance you would use this artifact name as the

identifier. Suddenly you can deduce the name of the application in SonarQube

just from looking at how it is named in git. If there is a predictable way of

navigating your tooling it is very easy to add dashboards and metrics later on

without manually mapping an applications integrations to different tools.

The cost with this approach is that it becomes crucial to document these conventions and to automatically nudge people if they aren’t being followed. Usually it is easiest to provide these integrations for free without the need for configuration such that every build using the golden path will automatically create a report in SonarQube for instance.

Defining your success metrics

At this point we have an idea of how we want to connect these pieces together to form an intuitive and useful pipeline. But we also need to be able to see how we are doing. Are we getting anywhere?

The dashboards we started with serve as a basis for this, they have shown us our current state, and now we have to adapt them to show change. Are we deploying more often, do we have less production issues etc. But we should also make sure to visualize if people move away from the tooling we’ve provided. If everyone starts overriding a certain configuration, maybe the default needs to change? If everyone disables SonarQube checks, maybe that tools isn’t working for us?

Work on a platform like this will never end, but it will change and it’s crucial that we’re able to adapt when the need of our developers change. Good dashboards, regular stakeholder meetings and easily accessible support channels are key to being on top of this.

You should also make sure that you know what management is hoping to get out of your efforts, and what they expect you to deliver. You might have to give them a reality check or even encourage them to think bigger. You won’t get far if you don’t have buy in from your key stakeholders.

Finally there should be metrics that display the efforts of the teams. Did someone just squash 100 bugs? Well salute that angel of light with banners, bread and cheese! Great efforts should be displayed to everyone and focus on the team or the person. Problems or missing configuration should be shown to the relevant teams only and be presented more as a todo list. You get the idea, use the carrot, not the stick. Even if you are working with Dwight Schrute. Not only does this tend to encourage the teams on display, but when other people see that someone is using your platform and nailing it, they might want to try it too.

Eat your own dog food

At this point we know where we are, where we want to go and we have an idea about how to get there. So we start working and setting up some tools and integrations. It’s very tempting to start on boarding teams right away. But there will always be bugs, and if you make your users your testers they will not trust you. Trust is everything for a Delivery Platform. We are nannies and the developers are leaving us with the responsibility of taking care of their babies. We clothe them, check that they are warm and secure and safely send them to school. If we can’t be trusted, we are useless and wasting our time and everyone else’s time.

As far as possible I like to use our common tooling to deploy all of our own platform services. And as an added measure it’s useful to setup a skeleton application to serve as a blueprint for how to get started. This application should be built frequently so it can function as a canary to alert us if we’ve changed something that might brake things for other users.

Low hanging fruits

Setting up a platform like this is costly, both in terms of money but also politically. You will most likely feel the pressure to deliver value fast. One common problem I’ve hit is that to get the most impact you target the big players first. They will make for a great example of our success and surely, if they are on boarded, the rest will be super easy?!

There’s been a few key problems with this approach in my experience. Firstly, the earliest adopters will always find the most bugs. Second, the biggest teams tend to be the most mature in that they have already had to make some of this tooling them selves. This means that you are not only on boarding them, you are also migrating them. This tends to add quite a bit of overhead because you can’t just lift and shift, you have to take them on board step by step, maybe breaking with some conventions along the way. This often triggers even more bugs and corner cases. And since these teams already have something in terms of support tools, they might not be particularly motivated to spend time on boarding something new.

Instead I’ve experienced a lot more success starting with the smaller teams. They are usually less coupled with existing infrastructure and tend to have less tooling available. Tooling like the platform you are offering might be something they could only dream about before, but now they can have it for free. If you start with these teams you can control the pace and your use of resources for on boarding much better. You can also iron out the most common problems before tackling the bigger more complex teams. Because there will always be use cases and situation you had not planned for.

Don’t underestimate the human aspect

Something that really surprised me early on was how some teams that were in dire need of migrating from existing unmaintained platforms or tooling were reluctant to do so. They seemed to agree that what we offered would help them, and they hated their existing setup. But we kept getting blocked when we tried to on board them. Eventually we figured it out. They had invested a lot of time and effort into their old setup, and they had a few nifty features that we didn’t support. We hadn’t payed much attention to these features initially because they seemed trivial and considering all the new features they were getting.. Well. We didn’t pay attention. When you’re replacing something old with something new and better it’s not better if it doesn’t match the existing feature set, because that means more change for the team. It might seem trivial from a technical point of view, but we humans don’t think that way. We have an aversion to loss, or rather loss aversion. We prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains.

This is just one example but you’ll find that psychology plays a huge role when you are dealing with people and change. I highly recommended the book Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman. It casts some light on cognitive biases and how we tend to think either reactively and instinctively or logically and analytically depending on a multitude of factors. It’s crucial that we can identify both ways of thinking and even appeal to logic when needed.

Unified support channels

So we’ve started to on board teams and everything is going great! But what is this? Complaints?! Bugs?! MUTINY!?

How should your users initiate contact when they have an issue, or have found a bug, or they need a new feature? The platform team might not even be just a team at this point, it might be several teams scattered around the globe.

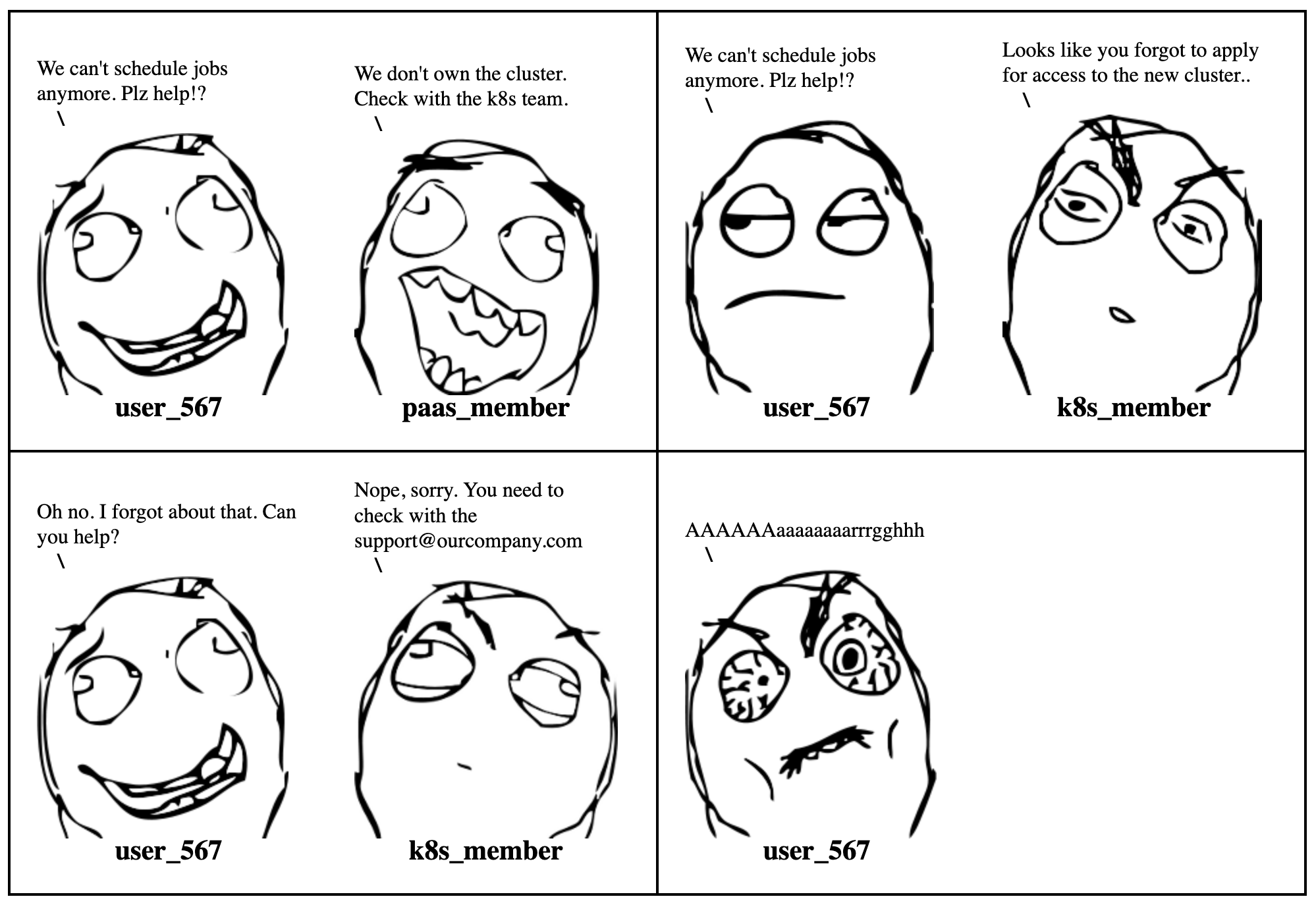

An approach that seemed to work was to have every platform team do their own support. We would create Slack channels and Jira projects, so bugs and feature requests would go into Jira, and incidents and discussions would go to Slack. At first this worked great. Our users were really happy to be able to reach us on slack, and most of them were really motivated to use our tools so they would help with pull requests when something was wrong or missing. After a while though slack got really busy, and we started directing people towards Jira instead. That helped a lot but we weren’t getting as much tickets as we would have expected. The problem, we later found, was that our users didn’t know where to report their tickets. Someone had problems with logging, was that the responsibility of the observability team? The runtime team? Or maybe the team in charge of PaaS configuration? If they submitted their ticket one place they quickly got forwarded somewhere else. This became a nightmare in terms of user experience, because our users weren’t getting the right help.

Our solution was to create a unified Help Center. It was basically just a confluence page with a form to create a ticket in a Jira project. But it gave our users a single point of entry. No need to guess where a ticket should be directed. The ticket followed a template asking some key questions which would give the person on call for the Help Center enough information to route it to the relevant team. Serving on rotation for a help center like this isn’t glorious, but it solves a lot of problems, and it makes the user experience a lot better. A bonus is that you learn a lot about the tools provided by neighboring teams.

With this experience in hand we also became a lot more focused on creating a unified experience for our users. If everyone has to visit 5 different tools to see how their application is doing in terms of vulnerabilities, code smells and deployments they are less likely to go look. If you have one entry point that fans out and lets people drill down into the metrics they are much more likely to use it often.

I guess that’s all there is to say about that

No not really. There are probably a thousand things to say about building a Delivery Platform, but I think I’ve touched upon a few key elements at least. Seeing teams adopting your tools and increasing speed and confidence as a result is a fantastic feeling. Being pulled into different teams with various tech stacks helping them debug corner cases and oddities is extremely rewarding and you learn so much. It is the dream job I never knew I wanted until I suddenly had it.

If you have any insights, disagreements or comments please join in on the discussion over at reddit.com/devops or hackernews.